Pico de Orizaba marks the high point of Mexico at an altitude of 18,491′. The peak seemed like a logical progression from my previous high of 15,774′ on Mont Blanc and a worthy testing ground for higher elevations. I was curious to know my body’s reaction to the thinner air, and more importantly, to find out if I’d have any adverse reactions to it.

Truth be told, reaching the summit of Pico de Orizaba was somewhat of a secondary objective as I was actually more interested in experiencing the effects of pushing fast up into high altitude. My plan was to forego the recommended acclimatization period and go as high as possible, as quickly as possible. Perhaps foolishly, a part of me was actually hoping for a bit of AMS just so I’d better know how to recognize the illness for future pursuits among even higher peaks.

How it all unfolded:

- Arrive in Mexico City Airport

- Take bus to Puebla / check into hotel

- Wake up & rent 4×4 truck

- Drive to Tlachichuca

- Get lodging & gear from Servimont

- Prepare pack for next day

- Wake up and drive to Piedra Grande Refugio

- Begin trek

- Summit

- Descend to Refuge

- Spend night in refuge

- Drive back to Tlachichuca to return gear

- Drive back to Puebla to return truck

- Catch bus to Mexico City Airport

- Fly back to Monterrey

Like most of my endeavors, I didn’t research things quite as much as I perhaps should have. Luckily, everything came together without too much hassle or wasted resources.

The following were of particular importance:

- 4×4 rental truck was available

- Gear rental was open and had my size

- Road was passable

- Weather and glacier conditions were good

The Climb

Following Joaquin Canchola up the 4×4 trail, I reached the refuge at about 11 AM. After speaking with him for a short time, I finished readying my pack and began hiking.

Starting the hike at 14,000′ after having just driven from 9,500′ was surprisingly difficult. My heart was pounding out of my chest, my breathing was labored, and my legs felt heavy. I was still feeling pretty fresh though, and kept moving at a steady pace up the initial scree field. Passing a few descending parties, I gave my best ‘Buenas’ while struggling to not sound too winded.

About 30 minutes in I stopped to attach my water bladder hose and ended up accidentally stripping off the o-ring while pulling it out of my pack. This caused a significant leak which got most of my gear wet and forced me to unload my entire pack to dump the water out. Luckily I was able to find the o-ring at the bottom of the bladder sleeve, but the ordeal ate up a full 30 minutes.

When I finally got back to hiking, my lungs had started to feel a lot more open and efficient. Soon, I came upon a French group who’d just summited. They told me the glacier was in good condition but that they’d had hell staying on the correct path. Their advice to ‘stay left at every fork’ worked out well for me.

In short order, I found myself at the entrance to the ‘labyrinth’ (an amalgam of talus, boulders, and ledges below the foot of the glacier). Just as I reached this point, another party appeared and reported the same route-founding difficulties as the French group. This time the advice was simply “Just don’t lose the main path!”.

Personally, I didn’t think the route-finding was all that difficult. And for the most part, the cairns were actually more helpful than not.

When I reached the glacier I sat down to rest for a bit and recorded a couple of videos.

At this part of the ascent I reached a major turning point. It was here that I made the decision to fully commit to the summit and to only head down if I started to have ill affects from the altitude.

Not long after making that crucial decision, I was strapping on my double boots and fueling up on protein bars.

Glacier / Summit Gear List

- Rental Gear I Used:

- Double Boots

- Crampons

- Ice Axe

- Helmet

- Personal Gear I Used:

- Heavy Gloves

- Gaiters (Weren’t necessary)

- Sunglasses

- Headlamp

- Balaclava, Puffy Jacket

- Beanie (after sun went down)

- Gear I didn’t use:

- Down parka / puffy pants

- Sunscreen (hat mostly blocked sun)

My initial steps onto the glacier were met with equal amounts of stoke and anxiety.

Although my pack was now lighter (I left my approach shoes at the base of the glacier and now had my boots on my feet), the climbing required great effort.

I worked my way up the slope about 30 steps at a time and would stop to catch my breath and let my heart slow. Throughout this endeavor I made sure to stay mindful of my state of being. I was preoccupied with the notion of fainting (an unpredictable occurrence that had befallen me several times in the past in non-climbing contexts) and therefore maintained strict focus on my sense of presence. Of utmost importance were control over my center of gravity, confidence in my points of contact with the ground, certainty of my movements, and a never-wavering awareness of my body as a whole and the environment around me.

Having soloed on technical rock and alpine terrain I was not a stranger to the importance of focus. The elements which made this particular ascent taxing had to do with the unique aspects of the glacier. The only place that seemed secure enough to perform a self arrest was on the actual beaten track. The reason for this was due to the crushed nature of the ice created by the crampon traffic. Just off the trail, the glacier was essentially a 2 to 3 inch thick sheet of ice which could be punctured by the pick of the axe but would be difficult to use for self arresting if I happened to find my self sliding down it.

My worrying over losing my balance and/or randomly passing out kept me gripped pretty much the entire way up the glacier (which was a long way). Staying in the zone of complete focus was a tiring endeavor and was the mental crux of the route.

Up above 17,000′ feet, I was taking longer breaks, bending over the ice axe without shame to catch my breath.

An interesting thing happened about halfway up the glacier, I suddenly became lost in thought and frozen in place. There were a series of thoughts passing through my mind. Without seizing on a single one, they each flowed by like leaves floating downstream. It was a strange moment that was part meditation, part day dream. When I came back to my place on the glacier, I found that my body was in the exact position it had been before the thoughts came. Not a single muscle had so much as flinched and my center of gravity was still perfectly balanced over my feet and ice axe. My knowledge of which foot to move next and where to place it remained completely in tact. I stood for a moment longer contemplating my place on the side of the enormous slope and then perfectly executed my next step.

There were also two separate occasions on the ascent of the icy sheet when I became a bit worried that I might be moving up into terrain which would be difficult to reverse out of (as is the norm with most solos). These concerns were enough to prompt me to make practice turns to head down and to actually take several steps down the glacier. After rehearsing the descending movements along with feet and axe placements, I felt much more comfortable to continue trudging upward.

An additional phenomenon, no doubt related to altitude, occurred a couple times up above 17,500′ as I experienced these intense episodes of greatly altered vision. Even though a clear image of the phenomenon exists firmly in my memory, it’s hard to describe exactly how my perception differed in those moments. Each instance lasted between 30 seconds to a minute. The brightness of everything was intensified to the point that all texture disappeared, my peripheral vision was incomprehensibly white, and neon-pink bands of light shot out in waves from every angle behind foreground objects.

I recently rediscovered an old video of myself experiencing the same phenomena of altered vision and describing it in real time as I thought I might pass out. The description of the neon colored surroundings matches my experience up on the glacier.

My world appeared as an impossibly bright landscape interlaced between an up-close aurora borealis.

These changes in perception were a bit troubling, as they were reminiscent of previous times I’d fainted (presumably from an iron-deficiency). The seriousness of my location high up on the glacier did not go without notice but my decision to continue climbing was upheld and before long I was in view of the summit ridge.

Guttural stirrings could be heard from deep within the bowels of slumbering volcano and steam was seen wafting from various points on both sides of the ridge.

From this spot on the rim of the volcano, I wasn’t sure how much further away the true summit would be. My altimeter suggested that I may have quite a long hike ahead of me. Given the late hour I was quick to make haste.

Traversing along the ridge seemed effortless compared to the literal uphill battle I had just waged with the glacier. My breathing returned to normal and I was filled with the joys of conquest, knowing that the summit was within reach.

Beautiful pockets of clouds swirled all around and weaved intricate patterns among the various peaks of other volcanoes for as far as the eye could see.

Checking my watch at the summit, I realized that I’d actually been higher than it had been suggesting. This would be the reason why the summit ridge was so much shorter than I had first assumed.

I didn’t linger for very long on the summit, as the sun was quickly making its way toward the horizon. I snapped a few photos, put my base-layer and beanie on, and fixed my headlamp onto my helmet. It would’ve been nice to have stayed up there for much longer, soaking in the amazing scenery and replaying in my mind the efforts that had led me there.

Heading back down the glacier was incomparably easier than going up and the views in the evening sun were absolutely astounding. I was adorned in alpenglow nearly the entire way down and was completely drunk with emotion for having summited.

At times I felt my self becoming almost over confident of my place on the mountain and had to shift my focus back onto the fact that I still wasn’t safely down yet. It was of course still the case that if I were to slip and start sliding down, self-arresting would be a difficult task. Occasionally imagining myself slamming into the rocks below helped to keep my hubris in check.

As I made it closer to the base of the glacier the slope began to taper off slightly and I had the notion to perhaps practice a self arrest on the ice. I decided against this, however, mostly out of laziness and an urge to just get down off the mountain.

In the time it took to re-arrange my bag for the final descent, day had turned fully into night. Along with the darkness came much colder temperatures and a steady wind that pulled the remaining warmth out of everything it passed.

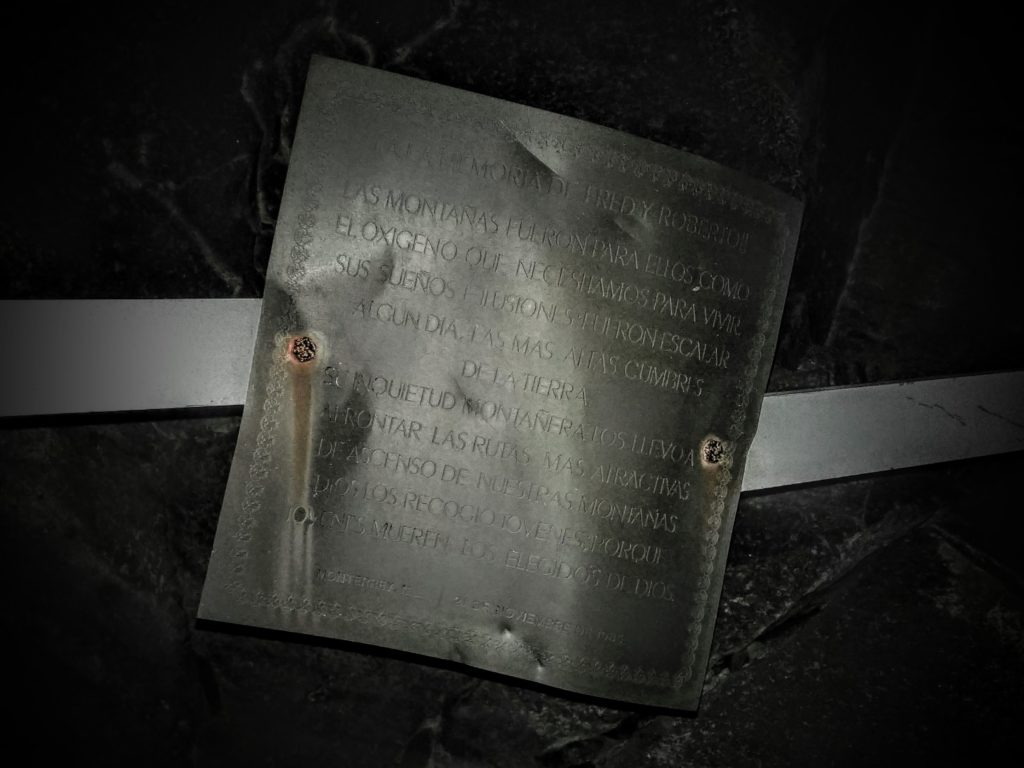

Not far from the glacier, a memorial to two climbers looms over the upper entrance of the labyrinth. Although I had passed by this just a few hours earlier in the daylight, there was something especially unsettling about coming upon it in the night. Despite their macabre nature, the crosses are a useful landmark on the way down as they stand just to the skier’s right of the labyrinth’s upper entrance.

The difficulty of route-finding through the labyrinth is greatly increased in the night and I assume it would be much worse in a snow storm. Here, the GPS track from my ascent was of great use and saved me an untold amount of time on the way down.

The trek down to the refuge felt mostly trivial save for a couple sections of down climbing in the labyrinth and a few loose sections on the lower scree field.

Headlamps could be seen gathered around the refuge as I made my way toward it. Knowing the night’s residents might retire to their sleeping bags at any moment, I quickened my pace to increase the odds of exchanging greetings with them.

Before long, I was standing below the front porch of the refuge engaged in conversation with 3 Mexicans who were spending the night there. Overcoming language barriers with translation apps, we spoke of my summit journey. It turned out they had seen me late in the day making my way up the glacier as a black spec among a giant white background. They remarked that it was quite late in the day for a summit attempt and that they’d been impressed by my efforts. They admitted to being relieved at the sight of my tiny silhouette eventually descending to the base of the glacier and they all collectively chuckled at the recollection of my headlamp swiveling wildly throughout the darkness of the labyrinth.

I was informed that 30 people were staying in the refuge this night and that in the morning they would be participating in a mountaineering course up on the glacier. I wasn’t sure if these three had waited up to witness my return, but only a few minutes after my arrival, each was entirely ready to turn in for the night.

One of my new friends offered me the use of an unoccupied sleeping bag among the bunks. I initially began to refuse and opt for passing the night in the rental truck, but shrugged my shoulders and accepted the generous offer.

It was a cold, uncomfortable night on the plywood platform laying among the tossing, snoring, and coughing inhabitants. My sleeping bag was too short for me and was somehow full of sand. The makeshift pillow I’d formed from my down parka held the comfort of a concrete brick and my shoulders and hips ached to no avail. Needless to say, I didn’t get much sleep that night.

Sometime around 1 AM, the majority of the slumbering occupants roused and, with a great commotion, readied for the hike up the volcano. A few sleepless hours later I rose at the faintest sight of the dawn’s light. I was soon met with my 3 friends from the previous night and in short order there was boiling water for coffee and breakfast. I helped them move some bags to higher locations on the upper bunks and spoke to them about their plans and about the mountaineering course.

Enrique, an apprentice guide, asked if I’d ever tried pulque. I said I hadn’t and accepted the small amount he offered me. It tasted sour and bitter, but not bad.

The sunrise was magnificently orange and illuminated the intricacies of several clouds as they let go large columns of rain. The streams of rain appeared as pedestals upon which the earthly nebulae rested.

It wasn’t long before I’d said my goodbyes and was driving down the dirt track away from the volcano. It also wasn’t long before I was high-centered over a large boulder at the crest of a hill.

I shoveled away dirt beneath the tires to make room for large rocks out of which I constructed a ramp that would elevate the under carriage enough to clear the obstacle. The improvised solution worked without incident, and I retrieved the vehicle without a single scratch or bent running board.

Puttering my way down through the forest I filmed my self driving, discussing the journey up Orizaba, sorting out what I’d learned, and reliving the excitement of the adventure.

After depositing my gear in the village below and saying goodbye to the hostel’s hosts I was on my way back to Puebla to return the truck, get on a bus to Mexico City, and catch a plane to Monterrey.

That same night I checked into a hotel just outside the Monterrey airport and woke the next morning to formulate the remainder of my itinerary.

I was due back in Texas to attend Thanksgiving at my grandparent’s but I didn’t want to arrive too early and ultimately I chose to pass my three remaining days in Monterrey rather than go home early or return to Potrero. I rented a car to expedite the retrieval of my crag bag which I’d stashed at Rancho El Sendero. Taking advantage of the vehicle, I also drove out to inspect La Popa, a large formation with lots of room for development. Getting back into Monterrey with all my luggage secured, I checked into my AirBnB, and spent the next couple of days relaxing and contemplating life.

The short stay passed in a blur and transitioned quickly into my bus journey back to the states. Soon, I was in Austin getting picked up by a good friend to do some cragging on the greenbelt before heading down to spend that night at my mother’s house.

Thanksgiving was spent with close family who were all eager to hear about my travels. I realized quickly that giving the abbreviated version of my climbing forays was no easy task. The parts of the adventure which were most exciting and meaningful to me were the exact parts I was too afraid to share with them. I was worried they wouldn’t understand my thrill at being all alone and utterly precarious up on the higher stretches of that peak. I didn’t know how to put my most meaningful moments into words that wouldn’t sound like deranged rantings of a mad man bent on self destruction. Instead I spoke little and just answered their questions as simply as I could.

When the conversation turned to spiders and snakes that I’d seen high on the walls in Potrero my uneasiness began to fade. I was relieved to move on from talking about my trials on the volcano, having not revealed those times that I’d been in real fear of serious consequences.